In a town called Tonalá on Mexico’s Pacific Coast, Jandy’s brother Tomaz was the first to get the fever.

“He presented with mild joint pain and fever for 4 days” Jandy recalls. “Then my mother, 74 years old, got it. She had inflammation in her feet, with pain in her calves and fever for days as well.”

It was in the heat of summer in 2016. There had been heavy rains and with them came an outbreak of what locals were calling ‘the mosquito disease’. Jandy’s family tried taking paracetamol but their condition did not improve so they resorted to cold baths and chilled drinks in an effort to quell the fever.

Jandy’s family had contracted chikungunya. A tropical vector-borne disease that has been increasingly prevalent over the past ten to fifteen years.

“In my case,” says Jandy, “I started with slight pain in the joints and fever. As the days went by, the pains all over the body increased. I reached a point where I needed help to walk, plus days of fever of 38 - 40°C, and a lot of pain."

The name chikungunya comes from the Kimakonde language, spoken by an ethnic minority in southern Tanzania. It translates to ‘that which bends’ or ‘to become contorted’, such is people’s physical response to the viral disease. It was first discovered in the 1950s but has risen to greater prominence in the last decade with improved monitoring, increased human movement and a number of serious outbreaks.

A painful reminder

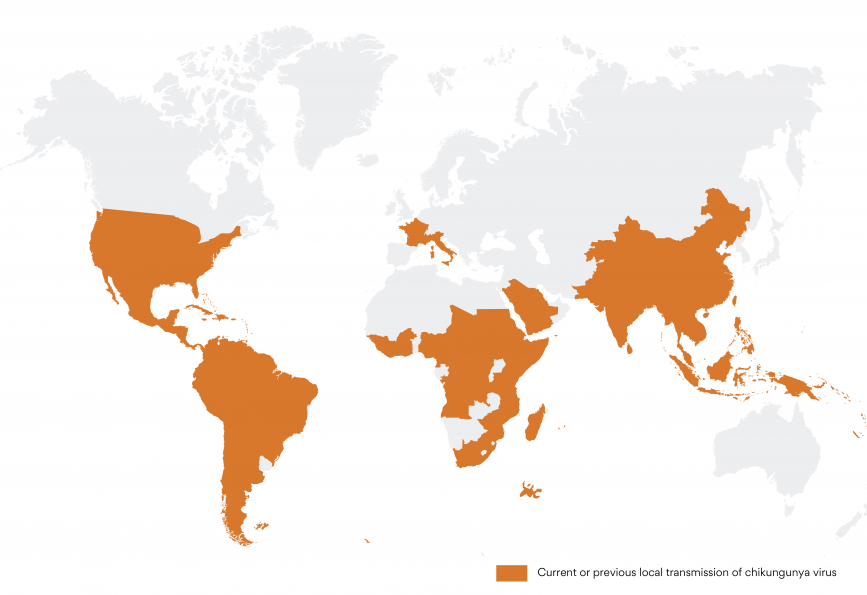

Chikungunya can be mistaken for dengue due to its similar symptoms of fever, body aches and fatigue. Like dengue, it’s predominantly transmitted by the Aedes aegypti mosquito and is now widespread throughout the tropical world. One telltale sign to help differentiate chikungunya from dengue is the severe polyarthralgia, or joint pain which is much more frequent with chikungunya.

In most cases, the debilitating symptoms will last a few days but there is a concerning pattern of victims suffering arthritic symptoms long after being infected. One study shows that around a quarter of patients reported persistent joint pain 2 years after infection.

Studies are ongoing to understand how chikungunya viral infection causes persistent arthritis. So far, we know that lingering symptoms are more common in patients who had a higher viral load or suffered a longer duration of symptoms during the initial phase of illness. Studies show that viral proteins were undetectable in these patients 2 years after infection, indicating that any long-term persistence of the virus is at low levels or in hidden sites. The most likely explanation is that the immune response to the initial chikungunya virus infection can lead to ongoing inflammation and joint soreness long after the virus has gone.

Jandy explains that the five members of her family who got chikungunya back in 2016 are still reminded of it by muscle and back pain. “Even after so many years we still feel pains sporadically in some parts of the body, not intense but a reminder of that terrible disease.”

No quick fix

As there is no vaccine for chikungunya and no sustainable measures for reducing mosquito populations, an alternative and effective solution to control chikungunya – and other Aedes transmitted viruses like dengue, Zika and yellow fever – is a growing priority for health authorities. Particularly in developing countries, and while COVID-19 continues to put pressure on vulnerable health systems.

Laboratory studies have shown that chikungunya infection and dissemination rates are significantly reduced in mosquitoes carrying the natural bacteria Wolbachia compared to Wolbachia-uninfected mosquitoes. There is also promising evidence from WMP’s project sites suggesting the method is effective against chikungunya in the field. Data from Niteroi in Brazil shows a 56% reduction in reported chikungunya incidence in areas where Wolbachia mosquitoes have been released.

Director of Impact Assessment for the World Mosquito Program, Katie Anders has been monitoring the long-term impact of Wolbachia interventions from 11 countries prone to mosquito-borne diseases.

“Many of WMP's partner countries have experienced explosive outbreaks of chikungunya in the past decade,” she explains. “All of our laboratory and field evidence indicates that high Wolbachia coverage will protect these communities from future chikungunya outbreaks, averting a large potential burden of acute and chronic illness.”

While WMP continues to accumulate data from field trials of Wolbachia releases from South America, Asia and Oceania, Dr Anders is confident the method could play a key role in mitigating chikungunya’s spread.

A solution as safe, sustainable and effective as Wolbachia is encouraging news for communities like Jandy’s, where lives and livelihoods can be critically impacted by an outbreak of this nasty ‘mosquito disease’.